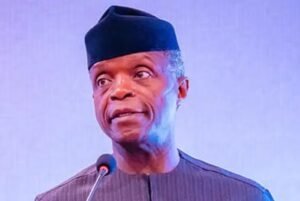

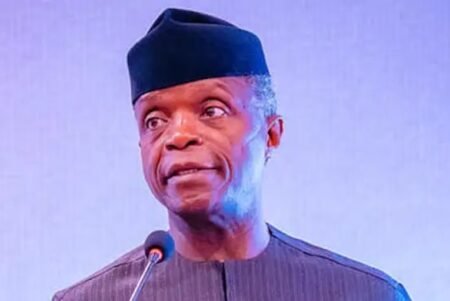

President Bola Tinubu has advocated for a fairer global financial system, claiming that powerful international credit rating organizations consistently underestimate the costs of borrowing for African nations, resulting in disproportionately high borrowing costs.

In an opinion piece, Tinubu said that Africa was “paying too much to borrow,” adding that it was no longer possible to ignore calls to close the “Africa premium,” or the discrepancy between the continent’s valuation and the true state of its economy.

The three main credit rating agencies in the world have a significant impact on investor behavior and Africa’s access to global financing, he said, but their evaluations frequently don’t fairly represent local economic conditions.

“Fitch, Moody’s, and S&P Global Ratings… wield outsized influence over Africa’s access to international capital. Their judgements shape investor behavior, yet they consistently misjudge African risk,” Tinubu wrote.

He asserts that these alleged misconceptions have serious repercussions. He referenced a United Nations Development Programme report from 2023 that estimated that “idiosyncrasies” in credit ratings cost Africa over $75 billion a year in lost financing opportunities and excessive interest payments.

Even though the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted that Africa would be the fastest-growing area on the globe this year, Tinubu pointed out that only three African nations presently had investment-grade ratings.

Plans to create an African credit rating agency, he added, were therefore a “necessary corrective,” especially in light of what he called the largest shortcoming of current international agencies: their lack of a strong local presence.

“How those judgments are reached and how much they count is left to opaque ‘analyst discretion,'” he added, adding that their models use quantitative data along with subjective assessments of political risk, institutional strength, and policy stability.

“Conclusions drawn from afar fail to capture local realities,” he added.

Additionally, Tinubu contended that dependence on these evaluations frequently magnifies global market cycles rather than representing the foundations of particular nations.

He pointed out that even when their reserves are robust and their fiscal buffers are adequate, commodity-dependent African economies are often downgraded when global prices decline or financial conditions tighten.

“Downgrades then become self-fulfilling, raising borrowing costs and straining public finances,” he wrote.

Tinubu supported the establishment of a continental ratings agency but emphasized that it must establish a worldwide reputation by providing investors with accurate, fast, and thorough data.

He pointed out that recent credit upgrades for Nigeria, which included rebasing GDP, disclosing additional budget papers, and incorporating hitherto off-balance-sheet central bank lending into official public debt records, were partially a reflection of increased economic data transparency.

Additionally, he cited policy changes, including the elimination of fuel subsidies and currency rate liberalization, claiming that these actions had aided in economic diversification and non-oil growth.

“The rest reflects hard policy choices, such as the removal of a wasteful fuel subsidy and the liberalization of the exchange rate,” he wrote.

Nigeria’s November dollar-denominated bonds were oversubscribed 5.5 times, according to Tinubu, who stated that despite these efforts, the country’s ratings still lag behind investor sentiment and reforms.

“Slow upward adjustments are commonplace across Africa, especially when set against the speed of downgrades,” he said, adding that smaller countries with less market visibility bear the costs most heavily.

A ratings agency that covers the entire continent, according to Tinubu, might assist in capturing the momentum of reform in real time, cutting down on delays that, he claimed, hinder African countries’ ability to swiftly access markets following the implementation of difficult policy changes.

“Africa’s success is not a regional concern but a global opportunity,” he wrote, noting that by mid-century the continent would account for a quarter of the world’s working-age population.

He also stated that while global capital markets would continue to rely on established agencies for validation, an African agency could serve as an early signal of progress and help ensure countries are able to compete on what he described as a level playing field.